Sampling confirms Harrisburg’s sewage overflow is polluting the Susquehanna River with E. coli

A related report finds Pennsylvania has ‘gone backwards’ in its effort to curb river pollution

Brett Sholtis / WITF

Ilyse Kazar stands along the Susquehanna river in Harrisburg next to a stormwater outflow while anglers fish nearby. Kazar, of Harrisburg, is one of the volunteers who collected water samples as part of the Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper's annual water monitoring.

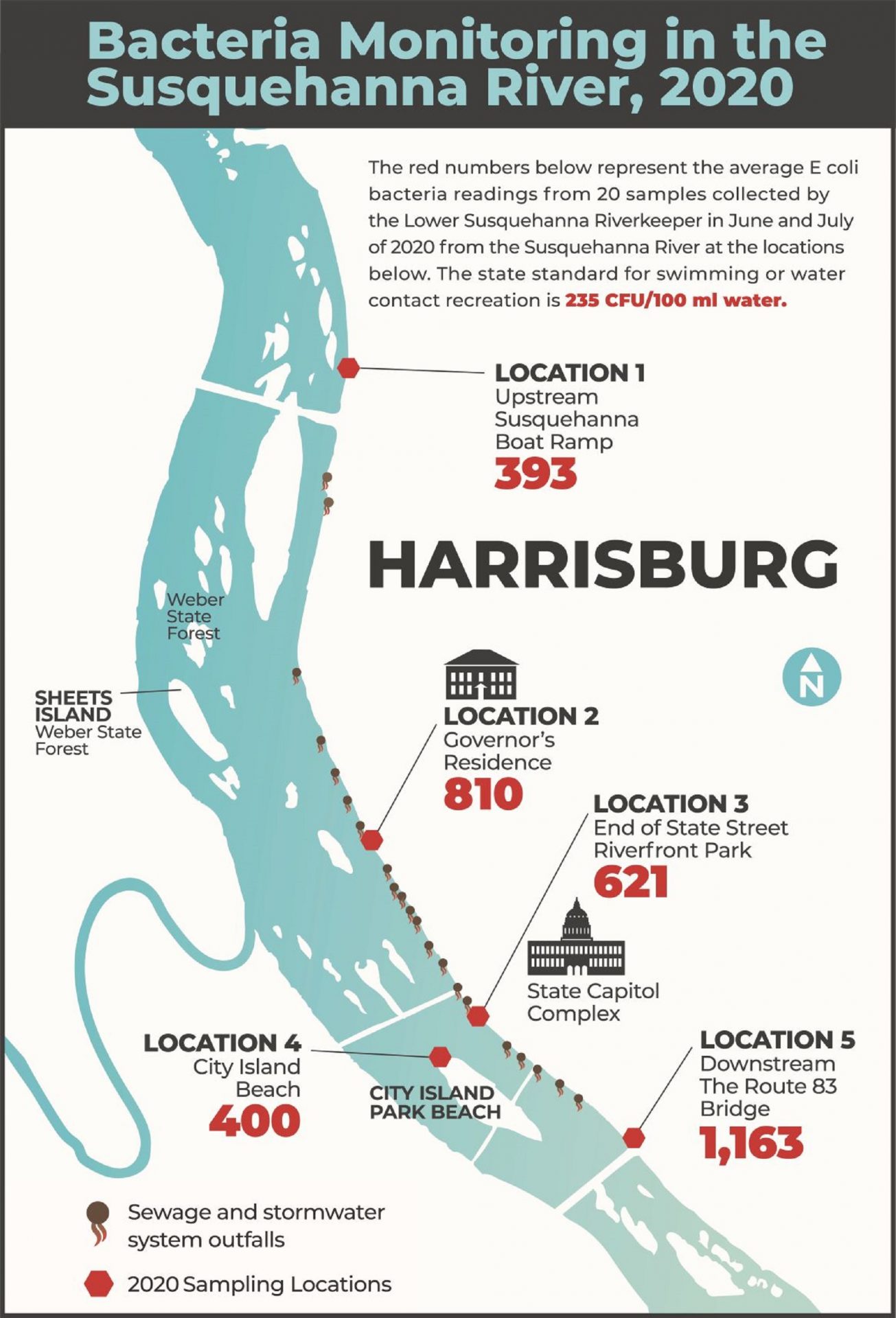

(Harrisburg) — Scientists found unsafe E. coli bacteria levels in the Susquehanna River during a third of the days this summer that samples were collected, according to a report from the Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper.

The annual testing, coordinated by the York County-based environmental nonprofit, also confirmed what it had suspected last year—that the city’s combined sewage and stormwater overflow system is adding significant pollution, according to Riverkeeper Ted Evegeniadis. Levels downstream of the city were almost triple what they were upstream.

“It’s a serious problem, and we’re calling on the city of Harrisburg to fix it,” Evegeniadis said. The office of Harrisburg Mayor Eric Papenfuse did not respond to a request for comment.

The city’s combined system dumps sewage into the Susquehanna River during periods of heavy rain—something Ilyse Kazar has seen first-hand.

The city’s combined system dumps sewage into the Susquehanna River during periods of heavy rain—something Ilyse Kazar has seen first-hand.

Kazar lives in Harrisburg and is one of the volunteers who collected water samples for the project. She said, while collecting samples she often saw “a scum of sewage” along the river—sometimes in the same areas where children were playing or people were fishing.

“Meanwhile I’m seeing the results come back with horrific levels of E. coli and fecal contamination,” Kazar said, referring to the potentially dangerous pathogen that can be transmitted through human and animal waste.

The water quality update was made public along with a new report, titled “Stormwater backup in the Chesapeake Region,” from the Washington, D.C.-based Environmental Integrity Project. That report says Pennsylvania has “gone backwards” in its efforts to reduce runoff that flows into the Chesapeake Bay.

Environmental Integrity Project spokesperson Tom Pelton said the Pennsylvania state government owns 40 percent of the property in Harrisburg and should fund a sewage and stormwater modernization project.

Pelton said he recognizes that the economic fallout from the coronavirus leaves states with less money to spend. However, infrastructure spending adds jobs at a time when many people are out of work.

“It’ll go to construction workers,” Pelton said. “It’ll go to engineers. It’ll go to construction firms right here in Pennsylvania.”

Brett Sholtis / WITF

Environmental Integrity Project spokesperson Tom Pelton stands for a portrait in front of the state Capitol, which, he points out, routes its sewage into the Susquehanna during periods of heavy rain.

Without a fix, the problem is only expected to get worse. The Environmental Integrity Project report notes that higher average annual rainfall related to climate change is expected to increase annual nitrogen and phosphorus pollution by about 3.5 percent. The state of Virginia has adopted pollution-reduction policies in response to that, the report states.

“In contrast, Pennsylvania and Maryland retreated in their proposed efforts to reduce urban and suburban runoff. This is significant because Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia account for about 90 percent of the urban and suburban runoff pollution fouling the [Chesapeake] Bay.”

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection is reviewing the report and declined to comment on its recommendations for statewide changes. In Harrisburg’s specific case, the situation is partly the responsibility of Capital Region Water, said DEP spokesperson Neil Shader. The company, which manages the city’s drinking water, is in a partial consent decree with federal agencies and is required to reduce stormwater runoff.

The state agency, along with the federal Environmental Protection Agency, “have been discussing long term control plan issues with Capital Region Water related to the requirements of the existing partial consent decree that is currently in effect,” Shader said.

Capital Region Water spokesperson Rebecca Laufer said the company “is committed to reducing combined sewer overflows that impact our waterways and is working towards a significant reduction that works within the financial constraints of city residents.”

“The challenges of maintaining and upgrading infrastructure that is more than a century old are difficult,” Laufer said. “We recognize the lack of past actions had detrimental impacts on the system, and Capital Region Water has been proactively addressing deficiencies.”

Brett Sholtis was a health reporter for WITF/Transforming Health until early 2023. Sholtis is the 2021-2022 Reveal Benjamin von Sternenfels Rosenthal Grantee for Mental Health Investigative Journalism with the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism. His award-winning work on problem areas in mental health policy and policing helped to get a woman moved from a county jail to a psychiatric facility. Sholtis is a University of Pittsburgh graduate and a Pennsylvania Army National Guard Kosovo campaign veteran.