For some people living with food insecurity, a meal is the first step toward getting help

Food outreach advocates say additional resources are needed.

Brett Sholtis / WITF

Outreach worker Aisha Mobley, at left, gives food and supplies to men living under a bridge in Harrisburg.

(Harrisburg) — A few minutes before noon, Kirk Hallett stood at the door of the St. Francis of Assisi Soup Kitchen.

A woman walked toward him from across the parking lot, and the 71-year old man held out an offering in a styrofoam tray: chicken, rice, beans and broccoli, all from the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank and cooked by volunteers at the church.

People showed up throughout the lunch hour in the sweltering July heat. Most walked. Some brought children. Another man parked his car, then walked across the lot with a cane. Many know Hallett by name, and he knows many of them by name as well.

Hallett started volunteering at Saint Francis more than 20 years ago. He says it changed him. He left his job selling construction equipment and formed a nonprofit called the Joshua Group that aims to help children succeed in school.

Related Stories

To him, volunteer work at the soup kitchen is part of the same mission as educating children.

“Our philosophy is, education is the anti-poverty program that works,” Hallet said.

Many of the same children who lack access to early childhood education also lack reliable access to food, he said. An estimated one in nine children lives with food insecurity, meaning they have limited access to nutritious, safe foods, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Hallet wants to help people succeed, but in many cases, the best he can do is offer food and a little conversation. He does both as he drives a daily route across the city.

“This isn’t just about driving around handing meals out,” he said. “This is about relationships, and I’m glad we can do that. Somewhere along the line, God is present with us in that conversation.”

Hallett is one of the many people who make sure food bank donations get to those who need them. He and others say food outreach is working, but there are limits to what it can accomplish without additional resources such as affordable housing and an investment in the city’s schools.

At Downtown Daily Bread in Harrisburg, development director Susan Cann said her team sees many people who have lost their homes. For them, food is often their first need, “but they need so much more.” Crisis workers, medical staff and others can provide some of that.

“Sometimes people are more ready to hear about different services,” Cann said. “Or they hear about it, it doesn’t work out the first time, but at least they know it’s out there.”

Cann estimates that half of the people who visit the Daily Bread soup kitchen live with a mental illness. Many have drug or alcohol use problems. Almost one in ten are military veterans.

She said demand for food dropped a bit last year. She thinks COVID-19 stimulus money played a role. But lately, demand for food has been ticking up.

There is also a dire need for affordable housing, Cann said.

She mentioned that after the Dauphin County District Attorney ordered police to clear out a long-running tent encampment near Market Square Presbyterian Church, it’s only gotten tougher for people who don’t have a place to call home.

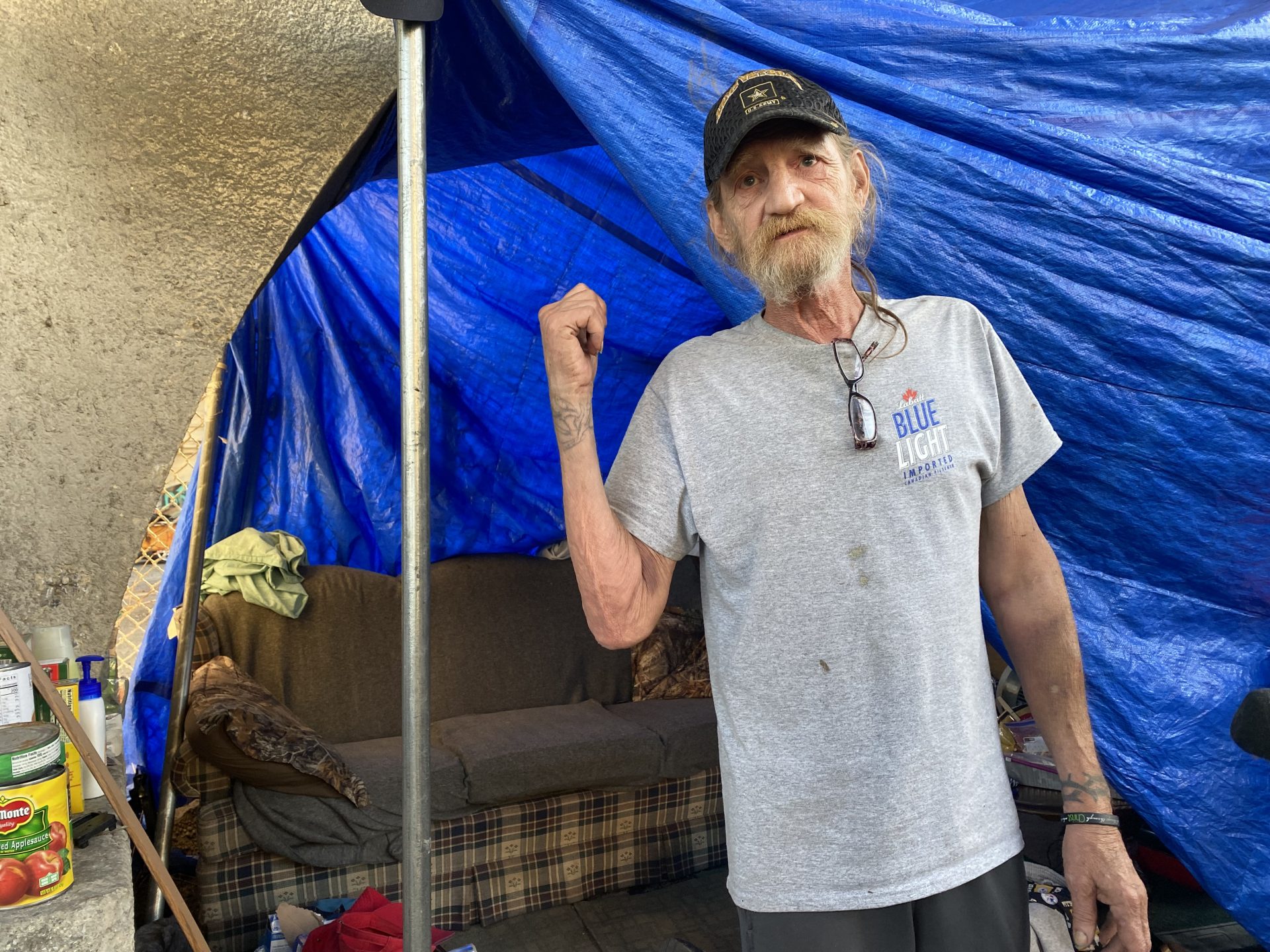

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

Pete Sollenberger gestures toward the shelter where he has been living for the past several months in Harrisburg.

This became during an afternoon spent with Kirk Hallet.

After handing out food for an hour at the soup kitchen, he dropped the tailgate on his 20-year-old pickup truck and packed it full with trays of meals.

He explained that COVID-19 changed his approach. They had to close down the dining hall. Food wasn’t getting to people. That was when he came up with his route around Alison Hill.

On this day, like most weekdays, Hallett dropped off about 20 meals at a house where military veterans live. Next he stopped by a street corner where people gather to hand out meals to anyone who wants them.

There he ran into people who had been displaced after the police broke up the tent encampment. With no options available near the church that had been helping them, some of them had trekked across Paxton Creek to Alison Hill.

Others ended up at Hallet’s next stop, about a mile away—camped under the Mulberry Street Bridge.

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

Christian Churches United outreach worker Aisha Mobley stands for a portrait in Harrisburg, July 22, 2021.

To Aisha Mobley of Christian Churches United, the space under the bridge is one of the few “sanctioned” encampments where she can direct people—meaning, police know about it, and social workers regularly visit it.

She explained this as she removed boxes from her van. She was helping a young man move after he was forced out of the Market Street Presbyterian tent encampment.

Mobley, who was a social worker for the Harrisburg School District for 12 years, said there are links between a poorly funded educational system, a lack of public health resources, and the problems of poverty, food insecurity and homelessness in Harrisburg.

The pandemic made these problems worse—but also led to more direct outreach with people.

After shelters closed last spring due to concerns about the virus, Mobley launched a push to provide face masks to people. That quickly turned into a broader effort to help people with things like laundry, housing and jobs.

Mobley said most of the people under the bridge have behavioral or physical disabilities, which means they either get Medicaid benefits or qualify for them. That’s something she can help with.

As she passed out sandwiches, muffins and fruit to people, she said providing food is a great way to build trust and get to know someone who might qualify for additional services.

Hallett mentioned this as well. During his route, a man told Hallett that a 67-year-old woman who lives in a tent near him was showing signs of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Hallett referred the man to a friend who could connect the woman with services.

Like Susan Cann at Daily Bread, Mobley said the biggest challenge is housing. Rooms are hard to come by. Average rooming houses cost about six hundred dollars a month. For Medicaid recipients who find a room, that leaves them with about a hundred dollars or so left for necessities.

“So when people say they choose to be out here? That’s the choice they’re making to be out here,” Mobley said.

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

Kirk Hallett, right, gives a meal to a man who is living under the Mulberry Street Bridge in Harrisburg.

For Pete Sollenberger, it’s no choice at all. He was staying with family until a few months ago. When that situation changed, he started sleeping in his car.

Eventually, the 61-year-old Army veteran built a shelter out of several tarps positioned under the bridge.

The longtime construction worker explained how injuries and health problems made it difficult to work. “I’d rather be in a house, or an apartment,” he said, adding that he’s trying to find housing. “Trust me. I’m too old for this.”

Sollenberger said he’s grateful for the abundance of food in Harrisburg—and for people like Kirk Hallett and Aisha Mobley.

“They come by everyday,” he said. “It’s really appreciated.”

Brett Sholtis was a health reporter for WITF/Transforming Health until early 2023. Sholtis is the 2021-2022 Reveal Benjamin von Sternenfels Rosenthal Grantee for Mental Health Investigative Journalism with the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism. His award-winning work on problem areas in mental health policy and policing helped to get a woman moved from a county jail to a psychiatric facility. Sholtis is a University of Pittsburgh graduate and a Pennsylvania Army National Guard Kosovo campaign veteran.